Though the H5N1 virus, commonly known as avian influenza or bird flu, was discovered in waterfowl in Southern China in 1996, it’s raising concerns again because it’s recently jumped from poultry to cattle, leading many to worry about potentially contaminated food supplies throughout the United States.

This bird-to-cattle crossover has never occurred before, and, within only a few short weeks, has already contaminated at least 20 percent of milk sold commercially within the country.

“It’s a virus that’s been around for a long time, but it’s been someone else’s problem if you’ve lived in the United States,” says Richard Webby, an influenza virologist at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital and the director of the World Health Organization (WHO) Collaborating Center for Studies on the Ecology of Influenza in Animals. “Now that it’s in America,” he says, “it’s found a lot of new hosts—in the form of cattle—and is wreaking havoc.”

Perhaps no one is better qualified to discuss this “havoc” than Webby. A New Zealand native, Webby was hired by St. Jude’s some 25 years ago to help study the first incident of H5N1 human infection following six deaths occurring in Hong Kong in 1997. Since that time, he has studied every mutation of the virus and countless cases across many species to get a handle on how it spreads, what effect it has on different hosts, and what humans need to be on the lookout for.

National Geographic spoke with Webby to understand the threat the virus poses and whether America’s food supply is in peril.

How the virus has spread historically

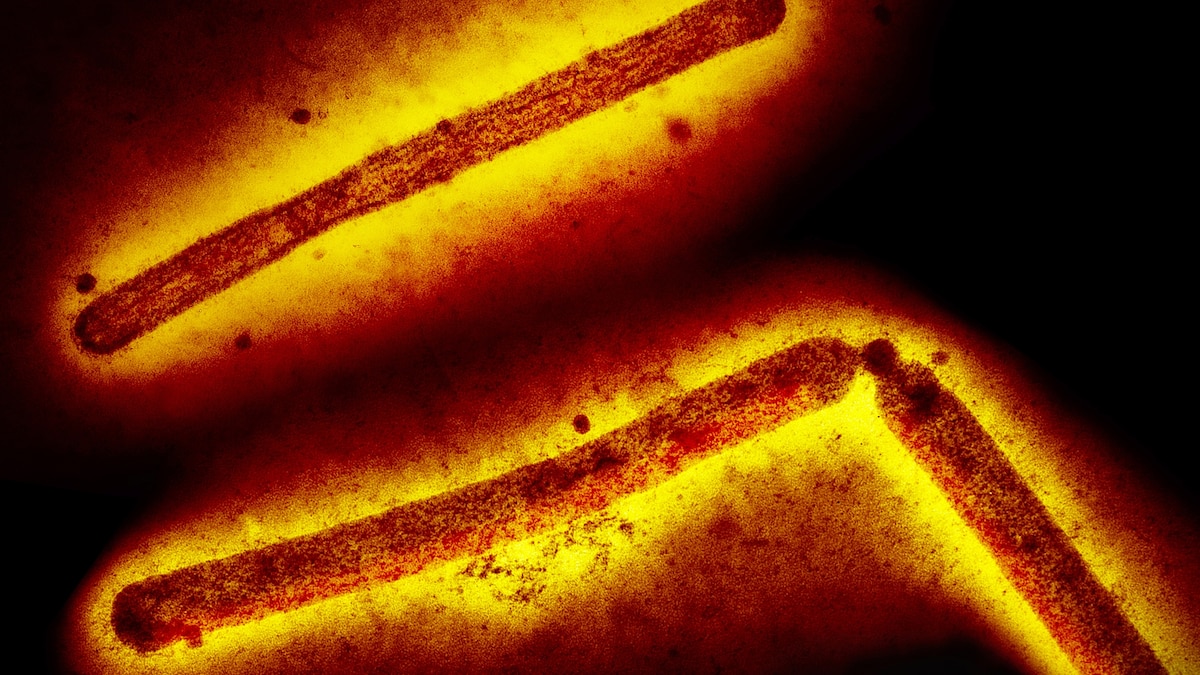

A type of flu virus that primarily infects birds, H5N1 can also infect humans. Such transmission is thought to be rare, however, as only 889 human cases of the virus having been reported worldwide since data began to be pooled in 2003.

But while the number of cases may be few, the lethality of the virus is worrisome, since more than half of those 889 infected people died.

Most such individuals were exposed in areas of the world where live-poultry markets abound—venues where birds are slaughtered and dressed for buyers to take home. Because infected birds are known to shed the virus through their saliva, blood, mucus and feces, Webby says that viral loads of H5N1 are commonplace in such markets, making human infection more likely.

Even in these poultry markets, however, he says that human transmission has been relatively rare when considering how many people frequent such venues and how prevalent the virus has likely been at each one for nearly three decades. He also notes that though the virus absolutely “has the capacity to cause serious disease and death,” it can also manifest with mild symptoms or no symptoms at all.

“If you look at the blood of people in Southeast Asia where these live poultry markets are so common, you’ll find a large percentage of people who have antibodies of this virus, suggesting that many of them may have had it, but didn’t know they were sick,” he says.

The situation has evolved now that the virus is also impacting people in new regions of the world and has infected at least 48 mammal species, including cattle, elephant seals, and even polar bears.

Because cows are a common food source, Webby says the fact that the virus can now infect and replicate within them is “very concerning.” And because this is uncharted territory, he says government agencies need to monitor the situation closely as scientists strive to get to the bottom of what’s happening.

WHO currently assesses the public health risk of cattle-to-human transmission of the virus “to be low,” but notes that their assessment “will be reviewed should further epidemiological or virological information become available.”

In the U.S., efforts to monitor the spread of the virus are being handled by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, which is monitoring contamination in dairy sources; the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which is overseeing how contamination is affecting cattle; and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which is watching for cases of human transmission of the virus within the country.

Should cattle be culled?

The first thing to understand is that no one knows how widespread cattle contamination is within the U.S. Webby says there have been instances where cows have died from the virus, but noted that some cows have been asymptomatic and that it’s not nearly as deadly among cattle as it is among birds. Therefore, “it’s possible that many herds are infected and not showing obvious signs of sickness,” he says.

You May Also Like

And while more than 131 million virus-exposed birds are slaughtered every year across 67 countries, Webby says that related cattle culling isn’t currently taking place in the country. This is because there’s no existing policy to do so since the virus was only discovered in cows at the end of March, and because it doesn’t seem to be an “all-systems infection” in cattle as it is in poultry. Indeed, in most cases, infected cows have manifested only mild symptoms, and most have recovered within a week to 10 days.

So far, the USDA has identified cases of H5N1 contamination in cattle herds in Texas, New Mexico, South Dakota, Colorado, Idaho, Michigan, Ohio, Kansas, and North Dakota, but Webby says extensive nationwide testing hasn’t been done yet and that herds in other states are also likely contaminated. What’s more, he says it isn’t known how transmission is occurring between cows; the current theory is that contamination may be occurring through dairy equipment involved in the milking process. “Once we can get a handle on how it’s spreading, there’s a good chance we can stop it,” he explains.

He also says there’s no proof that any beef products have become contaminated with the virus, and that freezing or cooking the meat would likely kill any active remnants of H5N1 if virus-contaminated beef existed.

“This is actually a pretty wimpy virus,” he says. “It’s very sensitive to elevated heat or any changes in pH levels, and it really doesn’t like being outside of a host.” Because of this, he says the only food supply issue he’s currently concerned about stems from people drinking unpasteurized milk.

What about milk contamination?

The FDA released a statement in late April saying that the country’s commercial milk supply is still considered “safe.” This is because fresh milk is pasteurized—an industrial process of heating milk to a high enough temperature to kill harmful bacteria. Also, milk known to come from sick cows is being destroyed as an added precaution.

The USDA is preventing further spread of the virus by requiring any of the country’s estimated eight million lactating dairy cows to be tested for H5N1 before crossing state lines.

Alongside such efforts, a team of researchers that Webby works with at Ohio State University, have tested more than 150 commercially available milk products and found particles of the viruses “in about 40 percent of the samples they collected,” says Webby.

Trying to help the team by providing a negative control sample to compare the positive samples to, Webby purchased a bottle of milk from his own local supermarket in Memphis and was surprised to find particles of the virus in that milk as well—revealing just how widespread dairy contamination likely is.

Further testing revealed, however, that the pasteurization process had indeed inactivated the virus, so the particles present posed no real danger. “That bottle of milk is still in my refrigerator at home and I’m still drinking from it,” Webby says.

Matters are different for unpasteurized milk drinkers, however. “Though we haven’t seen any cases of this happening yet, if someone was to drink a cup of unpasteurized milk that a large amount of the virus was present in, there’s a good chance they’d get infected,” he says. “Because of this, I would absolutely be concerned about drinking unpasteurized milk right now.”

Should humans be worried?

The CDC notes that only one human case of the virus has been reported in 2024, and that individual had been working closely with contaminated cattle. He experienced only mild symptoms, primarily conjunctivitis—commonly referred to as pink eye. In 2022, another American was also infected with the virus, but that was presumably related to poultry exposure, as no cattle infections had yet been discovered. These are the only two known human infections of the virus within the country ever. In April, Vietnam also reported a cattle-related human H5N1 infection, making it only the second cattle-related infection worldwide.

The CDC shows that human infections of H5N1 generally occur when the virus gets into a person’s eyes, nose, mouth, or is inhaled. This can happen when droplets or small aerosol particles of the active virus in the air are breathed in, “or possibly when a person touches something contaminated by (the virus) and then touches their mouth, eyes or nose,” the agency notes.

Because of this, Webby says the people who ought to be most cautious at this point are any dairy farmers who could be working with infected cattle and anyone drinking unpasteurized milk or eating unpasteurized milk products.

He says it’s possible for things to change, however, as the virus has long been limited to birds and its crossing into cattle could lead to a more infectious variant.

“This is still very much a bird virus that would much rather be replicating in birds,” he says. “But the concern is that while it was mainly only replicated in birds, it had no pressure to change to be more infectious to humans,” he explains. “But now that the virus has spilled over into mammals, there are theoretically more opportunities for it to mutate into something that becomes more infectious for mammals, including humans.”

Unless that happens, though, and unless the public milk supply is deemed unsafe, he says there isn’t cause for alarm. “At this point, there’s no evidence from the information that’s been provided that the virus currently circulating in cows is any more infectious to humans than the one that’s been circulating in birds for nearly 30 years—and we already know that transmission risk is very low.”