By BAGEHOT

A PATTERN is emerging in political journalism. Whenever something can be interpreted as a rejection of the facility, or a win for authoritarianism, or an accomplishment for arrogant, braces-twanging bombast– or some other shift the author does not like– the topic is credited a worldwide Trump-ite transformation. Frequently this comes without subtlety.

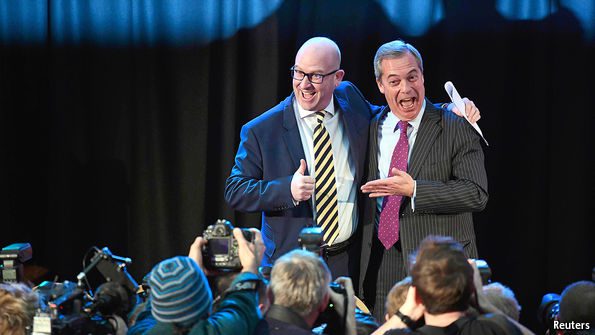

Take today. On Monday actions to the election of a statist, pro-death-penalty MEP as UKIP leader followed the pattern. “Paul Nuttall: Poundshop Trump” ran one much-shared tweet; “Trump minus the wig” was another. Today Tim Farron, the leader of the Liberal Democrats, called his centrist celebration’s success in the Richmond Park by-election a “repudiation” of Mr Trump. On Sunday Italians might decline their federal government’s proposed constitutional reforms: “Italy has a Trump of its own” declared a Haaretz heading of the leader of the “No” project. On Sunday a governmental election in Austria might produce Europe’s very first reactionary head of state given that 1945. “Austrian nationalists wish for a ‘Trump bump'” worried today’s Washington PostHardly a day passes without politics someplace being associated with the president choose’s shock triumph.

Enough. It’s not that the contrasts are essentially incorrect. A populist, nationalist wave is sweeping the West. It involves the recession, globalisation, automation, migration, stagnant salaries, social networks and a less deferential culture; albeit in considerably differing percentages in various nations. Each circumstances of this shift stimulates on the next. To draw contrasts is reasonable. Crucial ideological and market qualities unify Mr Trump’s election, Britain’s choose Brexit, Mr Nuttall’s potential customers in northern England, Norbert Hofer’s in Austria and those of the “No” project in Italy. There is likewise the Dutch vote in April versus the EU-Ukraine association contract, the increase of hard-right celebrations like the Sweden Democrats and Alternative for Germany, authoritarian leaders like those of Hungary and Poland, motions like Pegida and the Tea Party.

The issue is that speaking about the resemblances in between these forces is all the rage, however speaking about their distinctions is not. Which matters. For the resemblances inform a lovely story: among normal folk all over losing persistence with their self-serving rulers; the private-jet-bound Davos crowd, the Clintons and Blairs, the Goldman Sachs employers and their smooth lobbyists. The resemblances tell a 1989 for the 21st century. The neglected distinctions, nevertheless, are simply as striking, and all-together less lovely.

They inform regional tales that provide the populists less credit. Tales of Hillary Clinton’s failings and those of her project, of David Cameron’s limitless usage of Brussels as a punch bag, of the organisational weak points of Britain’s anti-Brexit project, of the liberal arguments versus Mr Renzi’s constitutional reforms, of UKIP’s dysfunction and Nigel Farage’s failure to win even a beneficial parliamentary seat in 2015. Each of these legends specifies and rooted. Each, too, recommends that the populists in concern are not rather the vibrant heralds of an unstoppable modification that the resemblances in between them may suggest.

The distinctions make complex the story of an unexpected wave of modification. They expose that while Ms Le Pen might make the 2nd round in the French election next year, her more overtly conservative daddy managed the exact same accomplishment in 2002. They expose that while Mr Hofer might win the (mainly ritualistic) Austrian presidency on Sunday, his celebration has actually been a recognized force in his nation for years and ended up being the majority of a union federal government as long earlier as 2000. They ascribe Italy’s “Trump of its own” to an anarchic Italian custom that precedes not simply Mr Trump’s election win however likewise his birth. They expose that the post-communist nationalism flourishing in main European nations like Hungary and Poland has its roots not before the turn of the years however before the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Most notably, the distinctions belie the easy options proffered by some. It is commonly stated that the “liberal elite” can not perhaps comprehend the modifications through which it is living due to the fact that it does not comprehend the hard-up strivers driving them. Never ever mind that this sort of believing delivers the classification of “elites” to the similarity Mr Trump, a billionaire, and Nigel Farage, an independently informed previous stockbroker. It likewise stops working to discuss why Mr Trump’s success in ignored, rust-belt America is allegedly adjoining with that of his equivalents in, state, Sweden; a nation with a gleaming well-being state and a previous steel welder for a prime minister. Nor does it describe why Germany, speed the majority of the English-language press, still broadly likes Angela Merkel as it approaches 2m primarily Muslim incomers in a matter of years. Nor does it describe why the large bulk of hard-up strivers in America who take place not to be white chose Hillary Clinton (or perhaps acknowledge that she won the popular vote by over 2.5 m votes). As a theory of the times we remain in, the simplified, undifferentiated “worldwide Trumpism” story draws.

Many informing of all is how the populists hold on to the contrasts. In his triumph speech on Monday, Mr Nuttall promised to “put the terrific back in Great Britain”, a limp echo of Mr Trump’s “make America excellent once again”. The president choose has actually called himself “Mr Brexit” and offered Mr Farage a prominent trip in his golden elevator. Ms Le Pen and Mr Hofer commemorated both Britain’s vote to leave the EU and the American election result. The early morning after the Brexit vote Breitbart, the internal journal of the populist right, ran an editorial declaring: “It’s not simply Britain, you see. The transformation versus globalism is, well, international. Britain might be leading the charge, however insurgents and rebels from D.C. to Berlin are likewise hard at work torturing their elitist overlords.” Wonder why these individuals delight in such arguments?

The response is basic: unburdened by subtlety, the contrasts tend to obscure unpleasant regional scenarios, ask less challenging concerns and run the risk of indicating that any provided populist force instantly has its finger on the pulse of global occasions. Analysts who grab the “X is our nation’s Trump” line without acknowledging the distinctions are abetting the forces of authoritarianism on whom they might think they are helpfully shedding light.

Lots of resemblances do exist. The proof of the previous months is that populist success in one nation can “push, inform and perhaps even cleanse” populists in other locations (as I, hands up, composed the other day about Mr Hofer’s governmental run. This procedure and specifically its channels of interaction and mobilisation (like the identitarian motion, which I profiled herebe worthy of comprehensive examination. My point nevertheless, is that if these accounts of the resemblances, of the pattern, are not matched by accounts of the distinctions, then that imbalance enhances the populists. By all methods area and describe the pattern. Explain its limitations, too.