In October 2015, Connie Walker got an e-mail with the subject line “Alberta Williams.” Walker, then an investigative reporter at the CBC, had actually never ever become aware of Williams, a Gitxsan female who was killed in 1989, at twenty-four, and whose killer had actually never ever been captured. The message consisted of a single line: the name of Williams’s supposed killer.

Already, Walker had actually been attempting to inform stories about missing out on and killed Indigenous females and ladies for several years. Walker remembers checking out a newspaper article in 1996, when she was sixteen, about the murder of a Saulteaux lady called Pamela George, who was sexually attacked and after that completely beaten by 2 young white males. Walker was struck by how George, a mom of 2 kids, had actually been defined by the media just as a sex employee. She questioned why there were no Indigenous reporters covering the murder. She ended up being one, composing about George in her very first story for her high school newsletter.

At the CBC, where she started working as an associate manufacturer in 2005, then as a press reporter 3 years later on, Walker battled to cover stories about Indigenous ladies who had actually gone missing out on or been eliminated, leaving anguished households and limitless concerns, their stories frequently disregarded or rapidly forgotten. Much of them, like Williams, passed away or vanished along the Highway of Tears in northern British Columbia, however no place in Canada was safe. When the pointer about Williams’s supposed killer appeared, Walker had actually just recently assisted put together a database for the CBC of more than 230 unsolved cases throughout the nation, representing a portion of the almost 1,200 Indigenous ladies and women the RCMP approximated had actually gone missing out on or been killed in between 1980 and 2012. Supporters think the real figure is much greater, especially given that there is no thorough nationwide database for missing out on individuals. In Saskatchewan, where Walker matured, Indigenous individuals comprise 17 percent of the province’s population, however Indigenous females have actually represented around half of all female missing individuals cases given that 1948.

Persuading editors and manufacturers that these stories mattered, nevertheless, wasn’t constantly simple. Early in her profession at the network, while pitching a story about a missing out on Dakota lady called Amber Redman, Walker was cut off mid-pitch by a manufacturer who asked if she was discussing another “bad Indian” story. Her pitch had actually questioned why Redman had actually gotten so little attention compared to the nationwide headings about Alicia Ross, a young blonde lady from Markham, Ontario, who had likewise just recently vanished. The dismissive reaction she got was its own response. Eventually, Walker didn’t get to inform that story; it would be nearly 3 years before Redman’s body was discovered.

After she got the idea about Williams, Walker chose to attempt a various method to reporting the story, one that would link her death to the bigger epidemic of violence versus Indigenous ladies. When Missing & & Murdered: Who Killed Alberta Williams?a multi-episode narrative podcast Walker hosted and co-produced, aired in 2016, it was a breakout hit. In the program’s 2nd season, Finding CleoWalker assisted a household fractured by the Sixties Scoop discover what had actually truly occurred to their sis, who passed away a couple of years after being captured by kid well-being and embraced by a white couple. In December 2019, when audiences were anticipating news of a 3rd season, Walker revealed that she had actually left the nationwide broadcaster and signed up with Gimlet Media, a growing American podcast business. 2 years later on, Gimlet launched the very first season of Stolenwhich looked like a natural extension of Missing & & Murderedfollowing Walker as she examined the 2018 disappearance of a girl called Jermain Charlo in Missoula, Montana.

In Stolen‘s 2nd season, Walker moved focus to her own household as she looked for the priest who had actually abused her late dad when he was a young boy at St. Michael’s Indian Residential School in Duck Lake, Saskatchewan. The program has actually drawn in countless listeners, and in 2015, the 2nd season won a Pulitzer Prize and a Peabody Award. Walker had actually scheduled a speaking engagement in Seattle on the day the Pulitzers were revealed, and she was excitedly sharing the news with her manufacturer. “The taxi driver resembled, ‘Sounds like you got some excellent news.’ And I stated, yeah, we simply discovered we won a Pulitzer Prize. He resembled, ‘What is that?'” she remembers. “That was excellent, it brought me down to earth.”

Real criminal activity podcasts usually intend to resolve a secret by discovering an ending, by discovering brand-new proof or pointing a finger at the most likely killer, like a campfire story indicated to excitement and frighten. Native stories, too, are typically lowered to their terrible endings: a harsh death, a haunting lack. Walker goes in the other instructions, by revealing who an individual was before they ended up being a figure, stressing the intricacy and humankind of her topics while preventing the category’s propensity to sensationalize the most lurid information of their deaths. And she reaches back even further, to demonstrate how their life and death were formed by the complex tradition of manifest destiny that ripples throughout generations. In doing so, she achieves something much more extensive: by utilizing journalistic tropes to expose how little North Americans comprehend about the lives– and deaths– of Indigenous individuals, she is changing how we comprehend both today and the past.

Having actually won the 2 greatest awards in North American journalism and cultivated an enormous audience, Walker appeared to have unstoppable profession momentum as she got ready for the release of Stolen‘s 3rd season. Her story took an unanticipated twist: in December 2023, Spotify, which had actually purchased Gimlet in 2019, verified that the program had actually been axed (season 3 will still air). Walker, whose success represented a beacon of wish for despairing reporters, was now a sign of the occupation’s disconcerting, unavoidable collapse. And it brightened another secret too, this one about the market itself: If executives do not see the worth in a program as popular and seriously well-known as Stolen or Missing & & Murderedwhat will it require to encourage them that these stories deserve informing?

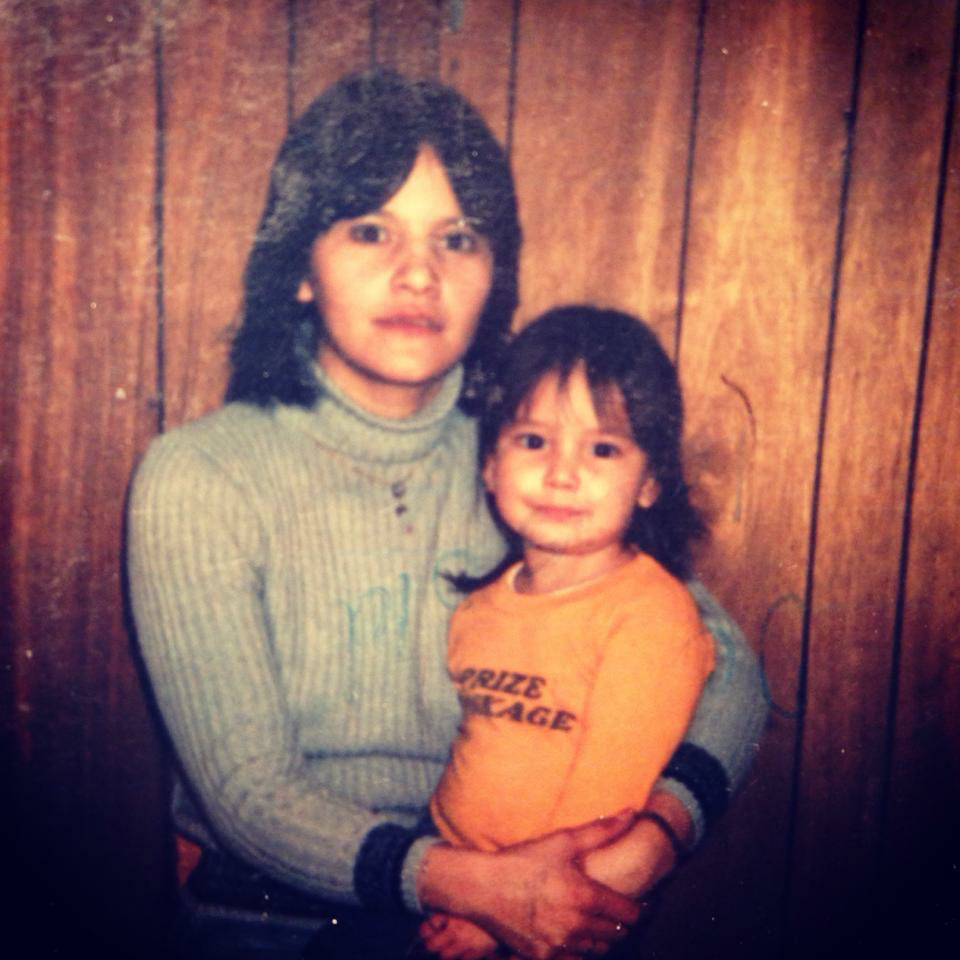

Walker invested the majority of her youth in File Hills, a tribal neighborhood of eleven First Nations about an hour’s drive northeast of Regina. Her moms and dads broke up when she was young; her dad was unpredictable and physically violent to her mom while they were together. After her moms and dads separated, she moved with her mommy to Okanese First Nation, where Walker’s close-knit household included her brother or sisters, her maternal grandparents, and lots of cousins, aunties, and uncles. “Nicknames are huge in my household,” states Walker, whose household calls her Totter; like with numerous labels, its origins doubt, however she’s quite sure it was created by a cousin who could not pronounce “Connie” when he was little. “I have loved ones where it wasn’t up until I aged that I understood, wait, that’s not their name.”

Walker was particularly close with her grandpa, and as a teen, she frequently invested her Saturdays chauffeuring him on long drives to yard sale. While at the Saskatchewan Indian Federated College (now First Nations University of Canada), she took a class that needed taping a narrative history. “So I established my camera and interviewed my grandfather that weekend,” she states. “That was the very first time I discovered that he went to Lebret (Qu’Appelle) Residential School when he was 6 years of ages.” All 4 of her grandparents participated in domestic school, as did her dad, however none had actually ever spoken with her about their experiences before. Walker, who believed she understood her grandpa so well, was shocked. “We ‘d invested hours together, discussing farming, speaking about sports. and here was this huge thing.” As in the podcasts she would later on produce, it was a discovery from the past that changed an as soon as familiar story, a secret indicating a bigger, more complex tale.

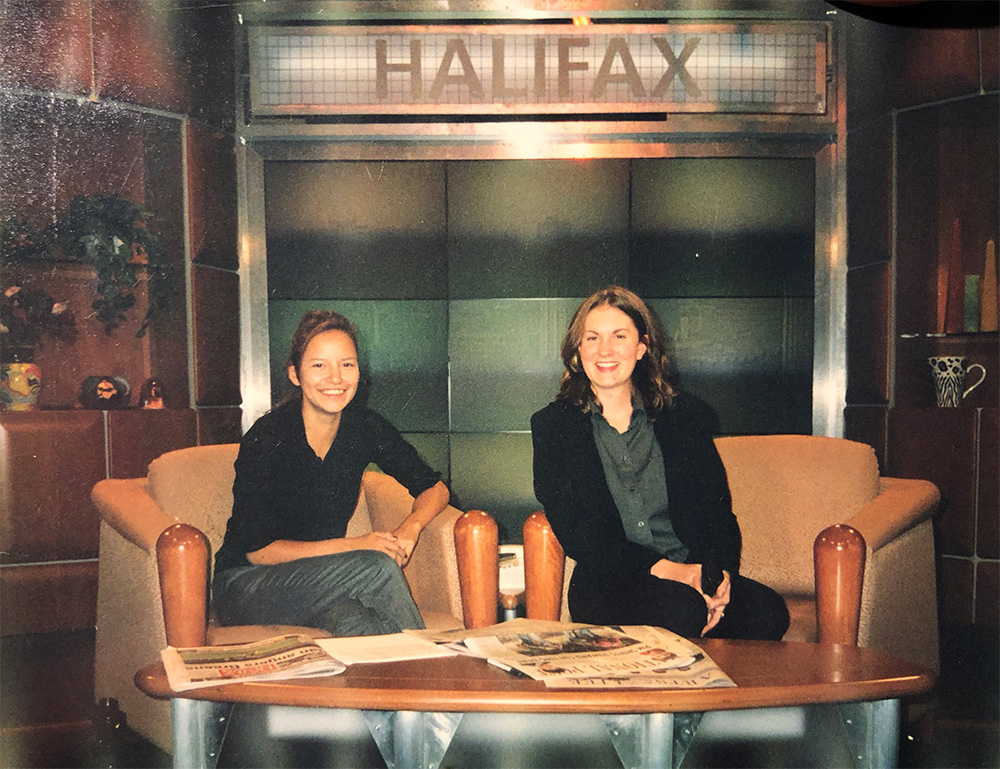

Walker never ever completed her degree. In her 3rd year at SIFC, she got a scholarship to intern with CBC Halifax as a chase manufacturer, reserving visitors for news sections. When, after scheduling a Mi’ kmaq chief to go over a fisheries conflict for a Monday sector, her manufacturer alerted her that Indians were responsible to get intoxicated all weekend and forget to appear. “I simply keep in mind the sensation of shame and anger,” she stated in a 2023 interview for the Warrior Life Podcastremembering how she scanned the space to see if anybody else had actually overheard, believing, It’ll be my word versus hersWhile taking a smoke break in the parking area one day, she fulfilled a manufacturer for Street Centsa CBC culture program for youth. They were searching for a brand-new host. The manufacturer asked her if she wants to audition. Walker did, and she got the task, leapfrogging from unsure intern to television host. She invested 4 years with Street Cents before moving into news, based out of Toronto. In 2012, she co-produced 8th Firea comprehensive four-part documentary about reconciliation, hosted by Wab Kinew, then a press reporter. The series included interviews with a varied selection of Indigenous individuals who challenged stereotypes and typical mistaken beliefs; audiences discovered that most of Indigenous individuals do, in truth, pay taxes– which domestic schools were not far-off history however had actually run in Canada up until 1996. The next year, Walker assisted produce CBC Aboriginal (now called CBC Indigenous) and entered a brand-new function as one of just 2 full-time reporters at the online platform.

Anishinaabe reporter Duncan McCue signed up with the CBC a couple years before Walker, however the 2 didn’t cross courses for more than a years. “The thing about CBC, when Connie and I both signed up with, is that the Indigenous personnel didn’t truly understand each other that well,” he states. There was just a handful of them, expanded throughout newsrooms, with little chance to work together or find how comparable their experiences and issues as Indigenous press reporters were. After CBC Aboriginal released, Walker started contributing stories, along with other Indigenous press reporters, consisting of Jillian Taylor, whose continual, delicate reporting on the death of fifteen-year-old Tina Fontaine assisted the public see her as not simply another victim however a kid who was deeply enjoyed and missed out on. That reporting didn’t come simple. “The individuals who held the handbag strings were not constantly eager to invest the valuable resources of our newsrooms on sending out individuals out into separated neighborhoods,” states McCue.

CBC Indigenous rapidly developed an audience, showing through growing readership that these concerns mattered not simply to Indigenous neighborhoods however to non-Indigenous readers also– something the group might show thanks to the current development of digital analytics. “I believe that the preliminary year of CBC Indigenous was a genuine eye-opener for the digital group, and for CBC News in basic,” states McCue. “Because they acknowledged– and we had the analytics to support it– that there was a hunger for stories that went outside the standard sort of judgment regarding what was relevant.” Within a year, Walker states, CBC Indigenous was outcompeting some provinces or areas of CBC protection in page views and social networks engagement, which shocked everybody. “When you’re attempting to rise in the newsroom, there’s a worry that you’ll be pigeonholed if you choose to concentrate on Indigenous stories,” states McCue. “But Connie stated: this is larger than me and my profession, this is something we require as a network. whereas previously, the CBC had never ever truly took a look at it that method.”

The success of CBC Indigenous made an undeniable case for the worth of Indigenous stories. Still, Walker had problem with the expectations of news reporting and the restrictions of the newspaper article, which concentrated on the instant and left little area for reflection or context. In 2015, while reporting on the murder of a fifteen-year-old Cree lady called Leah Anderson, she was irritated by how the story needed to be removed of subtlety and intricacy to fit a thirteen-minute television news section. “They remained in the kid well-being system, she and her brother or sisters. There was an actually alarming real estate circumstance,” she remembers. “There was so much going on and I seemed like we were needing to put blinders on and concentrate on one single thing.” Audiences were lastly seeing more stories about missing out on and killed Indigenous ladies and ladies, however they weren’t seeing how those stories were all linked.

A couple of months later on, when she got the e-mail about Alberta Williams’s supposed killer, the story was at first visualized as a two-minute news sector. Rather, Walker started to think of a various method of informing it, and stories like it– a manner in which would not simply concentrate on a last mind-blowing chapter.

At initially glimpse, Williams’s story seemed like one audiences had actually heard previously, one they believed they understood: another Indigenous lady whose life was ended completely along the Highway of Tears. As soon as Walker began examining, she understood there was an opportunity to represent one lady beyond the situations of her death and describe how and why the murders of Indigenous females so typically go unsolved, their households battling for responses to so lots of unanswered concerns. To inform that much deeper story, she would require more than a quick news sector.

Like nearly everybody else, Walker can trace her fascination with investigative, narrative-driven podcasts to Serialthe 2014 examination into the 1999 murder of Baltimore high school trainee Hae Min Lee and the conviction of her previous partner Adnan Syed. Walker can still remember precisely how she and her hubby feasted on the smash hit series. “We beinged in our living-room, on opposite sides– I was on a loveseat, and he was on the sofa– and we listened together in silence.” It was a discovery– a noticeably various method to inform stories, one that brought readers into the heart and procedure of an examination and drew them along as the press reporters chased after leads and weighed proof.

Walker had actually never ever done a podcast in the past, however she and her manufacturer Marnie Luke effectively pitched the CBC on turning Williams’s murder examination into a real criminal offense podcast that would surpass the murder to expose the intergenerational injuries and injustices that make Indigenous individuals so susceptible to violence. Walker states the 4th episode of the season, which moved focus to property schools, was a discovery for lots of listeners. “I keep in mind speaking with healthcare employees and individuals who were dealing with Indigenous neighborhoods every day, seeming like they didn’t understand or comprehend [the impact of residential schools] before listening to the podcast,” she remembers. Differing the main secret of Williams’s murder had actually not turned audiences off; rather, they were responsive, excited for a larger image. It was a “eureka minute” for Walker.

Despite the fact that Missing & & Murdered reached countless listeners and was chosen for a Webby Award, while dealing with its 2nd season, a supervisor informed her, “There will not be another podcast in your future. This is it. This is completion.” Walker hoped management would alter their minds if Finding Cleo Shown to be an even larger success than the. It was, however the CBC didn’t budge. “Every other media company is having a hard time to do lots of, lots of things with less and less resources, and they need to make actually tough choices,” she states. What makes investigative podcasts so appealing– their depth, their length, the time it requires to report them– likewise makes them pricey to produce, and Walker states she was informed her podcasts were too pricey and time consuming.

According to McCue, who calls Finding Cleo and Who Killed Alberta Williams? “2 of the most effective podcasts that CBC has actually ever had,” the monetary concern is just part of the response regarding why the CBC disliked Walker’s jobs. “I believe the loss of Connie speaks as much to the injustices that female reporters deal with in this company as anything else.”

Rather of another podcast, Walker was used an agreement as a press reporter with The Fifth Estatethe CBC’s flagship investigative documentary television program. After examining the agreement, she states, she asked if the wage was equivalent to that of the other hosts and found out that she would be paid less. She could not do it. She left Canadian media entirely. “As delighted as I was to sign up with Gimlet and to be able to focus specifically on podcasting, I believe, truthfully, I was actually unfortunate for a long period of time,” she states. “I seem like my work is an extension of who I am, and I constantly seemed like I was doing it for a larger function than my task or my profession– it was to attempt to assist my household and my neighborhood and other Indigenous individuals in Canada.”

In the early summer season of 2021, quickly after the ending of Stolen‘s very first season, The Search for Jermainwas launched, news broke that ground-penetrating radar had actually found presumed unmarked tombs on the premises of a domestic school in Kamloops, British Columbia. The scary news shook something loose in Indigenous neighborhoods throughout Canada. Survivors started sharing their stories of property school. “I keep in mind seeing relative who had never ever even stated the words aloud, a minimum of in my existence,” states Walker. “Now we’re making Facebook posts about it.”

One post was composed by her sibling Hal, and it had to do with their dad, Howard Cameron, who passed away in 2013. Hal had actually composed that when Cameron was a young RCMP officer, he had actually pulled over a presumed intoxicated chauffeur one night and discovered himself checking out the eyes of the priest who had actually abused him at St. Michael’s Indian Residential School. According to Walker’s sibling, their daddy pulled the male from his cars and truck and beat him on the side of the roadway, then repelled.

That summer season, she went back to Saskatchewan for a see. She taped interviews with other member of the family who had actually participated in St. Michael’s and attempted to find out if their recollections amounted to something larger. “I simply seemed like that was the method to handle the sorrow that I felt when I found out about his experience of abuse,” she states. “I was agitated by it for so long, and I simply seemed like I understood I wished to do it personally. Whether it was going to be a story or not, I could not see.” One of her manufacturers, Anya Schultz, asked a concern that brought the task into focus: “Why do not we attempt to discover the priest?”

“Lots of individuals are not going to wish to listen to an eight-episode podcast on property schools,” states Walker. “But if it’s framed with this engaging concern, then you’ll draw in more individuals who do not even believe they appreciate the Indigenous problems.” The reaction to the property school episode of Who Killed Alberta Williams? had actually shown that a single story, a single concern, might offer an entry point for audiences to discover that bigger context, one that might alter the method they comprehended the historical and modern forces that form Indigenous life.

The structure of the examination likewise served a crucial function for Walker. She had actually seen how her dad altered towards completion of his life; he quit drinking and attempted to apologize. He passed away before she ever actually had an opportunity to get to understand him, and in the interviews she carried out with her household members for Enduring St. Michael’sshe lastly started to comprehend him. “At a particular point, I understood I require the examination too,” she remembers. “This look for responsibility– it’s a method to transport my sorrow into anger. It’s the important things that moves me forward.”

St. Michael’s was simply among more than 130 domestic schools that ran throughout Canada throughout the twentieth century. It was opened in 1894 and was among the last to close in 1996– though for its last fourteen years, it was run by the Saskatoon District Chiefs. When Walker started broadening the examination beyond her household, she called Betty Ann Adam, a Dene reporter of nearly thirty years at the Saskatoon StarPhoenixand asked her to sign up with the production group and carry out interviews with survivors. Adam later on telephoned those survivors when the season began winning significant awards. One revealed her wonder that individuals were lastly discovering what had actually occurred to them as kids. “To be able to inform the survivors that individuals are hearing their stories, that they’re moved by the stories which they care. it provides the survivors some sense of the self-respect that features being heard and thought,” states Adam. “It wasn’t almost the item, the audio item that was produced. It was truly about this historic numeration and everybody stopping for a short time to take a look at this and go–this truly taken place“

“We’re all discussing reconciliation and what it indicates to fix up,” Walker states, “however we do not even comprehend the reality yet.”

For Walker, dealing with Adam in addition to Métis manufacturer Chantelle Bellrichard on Stolen was the very first time she belonged to a skilled Indigenous group. That experience is still unusual for Indigenous reporters. McCue, pointing out a 2022 variety study from the Canadian Association of Journalists, explains that about 8 in 10 newsrooms still have no Indigenous or Black personnel at all. “That requires to alter,” states McCue, who signed up with Carleton University as a teacher of Indigenous journalism in 2015 after twenty-five years at the CBC. “But what issues me more is the efforts that we make– that the CBC makes– to make sure that Indigenous personnel seem like they have a culturally safe office. Which requires to be more than lip service.”

When Stolen started examining the history of St. Michael’s, there was more attention being paid to domestic schools than ever previously, however there was likewise more rejection of their effect. More unmarked tombs had actually been identified at previous school websites throughout Canada, however some individuals had actually knocked them as a “scam.” Even previous prime minister Jean Chrétien declared he had actually never ever heard reports of abuse when he was minister of Indian affairs, before comparing his own boarding school experience to that of property school survivors.

One factor Canadians are still mostly oblivious of the scaries of domestic schools, as Walker’s examination discovers, is that most of survivor statements are locked away. More than 38,000 claims were evaluated by the Independent Assessment Process, developed as part of the Indian Residential School Settlement Agreement in 2006, which needed survivors to state the dreadful information of their abuse in order to be qualified for payment from the Government of Canada. Survivors were explaining criminal offenses, the procedure was not a criminal one, and no abusers were charged as an outcome. The resulting statements were sealed, safeguarding the personal privacy of victims– however likewise their abusers.

Due to the fact that they could not access those records, the Stolen group examined suits submitted by the survivors of St. Michael’s before the IAP procedure was developed. They discovered more than 200 accusations of sexual assault versus forty-five team member of St. Michael’s, covering around eighty years. What followed was a partial restoration of a single organization, its harsh and bloody history laid bare. And even as Walker expects the next season of Stolenpart of her is still thinking of all the stories in those suits, every one essential to a household much like hers, each ravaging in its own method.

In spite of how far Walker had actually come, in spite of the countless listeners and the awards, the remarks stuck around. “How numerous more of these stories can you do? They’re sort of the exact same story,” she remembers somebody asking her. It’s the method the stories have actually frequently been informed that develops this impression, due to the fact that many end the exact same method: a mistreated kid ends up being a distressed grownup; a lady vanishes without a trace; a murder case grows cold from disregard. Another bad Indian. By tracing those stories back to their starts, Walker exposes that they’re never ever basic and never ever the exact same. “Every household has a story,” she states. “Every single household, every lady, woman, guy, or kid is a chance to comprehend a larger story about Indigenous individuals, about Canadian history, about colonization.”

Starting in 2013 with Orange Shirt Day and after that in 2021 with the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, each year on September 30, Canada acknowledges the tradition of property schools, a tradition that is still mostly buried by the very same federal government that now honours domestic school survivors. The general public might never ever totally understand what survivors sustained at those schools– unless, obviously, those stories are informed. Over the last few years, Walker states, Canadians have actually risen towards reconciliation while avoiding an important action. “We’re all speaking about reconciliation and what it indicates to fix up,” she states, “however we do not even comprehend the fact yet.”

The 3rd season of Stolenbeing launched early this year, unfolds in the Navajo Nation, a location Walker didn’t understand much about, and she confesses’s a difficulty to report in neighborhoods where she’s an outsider. “Just due to the fact that I’m Indigenous and Cree from Canada, that does not always offer me any connection to the Navajo individuals,” she states. At more than 27,000 square miles, the Navajo Nation is the biggest booking in the United States; Canada’s biggest reserve, coming from the Blood Tribe First Nation, is simply under 546 square miles. Navajo is likewise the biggest country by enrolment, with almost 400,000 members. For the podcast, Walker and her group embedded with the Navajo police to comprehend the examinations into the disappearance of 2 ladies, which enabled them to inform a larger story about the crisis of policing in Indigenous neighborhoods. She compares her technique to that of The Wirethe 2000s television program embeded in Baltimore, and how each season concentrated on a various system in the city, like education or policing. It’s a design she was influenced by for her podcast work, structuring each season around a bigger problem that impacts Indigenous neighborhoods.

Her point of view on informing stories has actually progressed because she began as a reporter as her understanding of injury has actually progressed– including her own. Walker remembers how conflicted she felt previously in her profession asking relative of individuals who had actually vanished or passed away to relive their worst memories. The dominating thinking at that time was that any damage triggered by an interview was validated by the higher good of raising awareness about an unsolved murder, however press reporters weren’t trained to reduce the psychological influence on topics. Things have actually altered ever since, and Walker’s individual experience as both writer and topic has actually deepened her understanding of how to question an uncomfortable history. “Doing Making it through St. Michael’s seemed like a workout in trauma-informed journalism as a type of recovery,” she states. “If you are provided company, and you are appreciated in the informing of your story, that can be an empowering part of your recovery procedure.” In the last episode of Making it through St. Michael’sWalker shares that a person of her uncles, who was likewise sexually mistreated at domestic school, went on to perpetuate the cycle of abuse in his own household. Walker opens up about her own experience of sexual abuse. It’s a spectacular minute, an accomplishment of bravery however likewise of storytelling, one that exceptionally changes the listener’s understanding of the story they believed they were hearing. Fact, it reveals, can be a. course to recovery. Each of Walker’s podcasts has actually demonstrated how a single disaster– a missing out on mom, a lost sis– links back to the violence of colonization, which touched and continues to touch every Indigenous household. And every one defies expectations, showing that an awful and familiar ending is never ever the entire story.

That’s part of the factor she was drawn to podcasts a years back: drawing back the drape of an examination, exposing not simply the victorious discoveries however the doubts, the existential concerns, the frightening unpredictabilities. When Walker started her profession, there were couple of Indigenous stories being reported and less Indigenous reporters to cover them. There’s still a long method to go to inform them all and inform them. “I do feel this seriousness. For so long in my profession, I resembled, ‘I ‘d like to do that, however it’s not truly possible. There’s no interest, or that’s not my task, or whatever,'” she states. She’s a long method from the intern who was informed that Indigenous sources were undependable drunks, and the young press reporter whose pitch was as soon as dismissed as another “bad Indian” tale, however she’ll always remember them. “Now that I’m able to, I simply need to keep opting for as long as I can. Keep attempting to inform as numerous stories as I can. Due to the fact that as we’ve seen, there are no assurances.”

Soon before Walker signed up with Gimlet Media in 2019, the business was gotten by Spotify. In June in 2015, a couple of weeks after the Enduring St. Michael’s group won the Pulitzer and Peabody awards, Gimlet was liquified into a brand-new system called Spotify Studios. At one point, Gimlet represented the peak of the podcast boom, and its dissolution is seen by some as completion of a golden age. In between 2020 and 2022, one analysis discovered that the variety of brand-new podcasts every year had actually decreased by 80 percent while numerous existing ones were cancelled. In April 2018, Gimlet released a podcast called The Habitatabout a simulated objective to Mars, which co-founder Alex Blumberg later on referred to as both the network’s “most significant launch ever” and a monetary flop.

As Walker found out with Missing & & Murderedeven effective programs go through the deceptive financial calculus that guides the choices of media outlets, and a big audience does not always associate with a business’s understanding of success. It’s tough to measure the worth of a podcast that reaches countless listeners and alters the method they comprehend the tradition of domestic schools; it’s simpler to tally the cost savings of refraining from doing it. In early December, Spotify revealed it was getting rid of 1,500 tasks, or 17 percent of its labor force. (An extra 800 workers were released in 2 previous rounds of layoffs in 2015.) The very same day, the CBC revealed it was removing 800 tasks, or 10 percent of its labor force, in reaction to a predicted $125 million deficiency. Hours later on, it was verified that 2 of Spotify’s well-known podcasts had actually been cancelled, Heavyweight and Stolen

Even in a year of ruthless media layoffs, it was still stunning that Walker was dealing with the very same fate as countless other reporters: rushing for a grip in a collapsing market. Stolen’s unlikely cancellation laid bare the contradictions of a market whose choices are directed not by audiences or honors however by a little coterie of executives and financiers who have really various meanings of worth. Spotify, which saw its stock worth increase 7 percent instantly after the layoff statement, reported that third-quarter incomes had actually grown by 11 percent. In a memo revealing the layoffs, Spotify CEO Daniel Ek composed, “By a lot of metrics, we were more efficient however less effective. We require to be both.” According to Bloomberg, the platform was focusing its efforts on “certified programs that run year-round,” like The Joe Rogan ExperienceThat method leaves no space for investigative journalism, which can never ever be produced at the rate of a talk program and which by meaning needs depth and factor to consider.

For her part, Walker is prepared to adjust. Her profession has actually been a series of successes that confused long-held market beliefs about the absence of interest in Indigenous stories, with her pressing past those beliefs in order to link straight with audiences. In late October, she was sanguine and available to possibility. “I do not have a strategy,” she states. “I believe that my strategy is: I wish to keep doing this operate in one shape or another.” She likes the podcast format however states she ‘d likewise like to compose a book sooner or later and operate in movie and tv.

Stolen might be concerning an end on Spotify, however as Walker’s podcasts have actually shown time and once again, a story is constantly a lot more than its ending. Recall and you’ll discover it’s simply one piece of a larger image. Stolen has actually affected countless listeners and revealed them just how much they have actually delegated learn more about the lives and histories of Indigenous individuals. “There’s numerous various expressions that our stories can take, and as long as I’m getting to do this operate in some method, I seem like that’s the most essential thing,” she states. “We’re not returning to when individuals thought that our stories weren’t essential.”