flagstaff, arizona —

Kicking up a cloud of dust, the men riding bareback were in a rowdy scramble to be the first to lean down from atop their horses and grab hold of the chicken that was buried up to its neck in the ground.

The competition is rarely on display these days and most definitely not with a live chicken. And yet, it was this Navajo tradition and other horse-based contests in tribal communities that evolved into a modern-day sport that now fills arenas far and wide: rodeo.

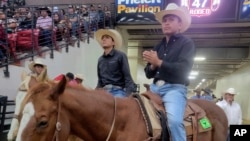

With each competition, Native Americans have made them decidedly theirs — a shift from the Wild West shows and Fourth of July celebrations of centuries past that reinforced stereotypes. Rodeo has provided a stage for Native Americans, many of whom had nomadic lifestyles before the U.S. established reservations, to hone their skills and deepen their relationship with horses.

“It was really a way to bring something good out of a really tough situation and become successful economically and, of course, have some joy and celebration in the rodeo world,” said Jessica White Plume, who is Oglala Lakota and oversees a horse culture program for the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation in North Dakota.

The sport was born in the mastering of skills that came as horses transformed hunting, travel and welfare. Grandstands often play host to mini family reunions while Native cowboys and cowgirls show off their skills roping, riding and wrestling livestock.

One of those rising stars is Najiah Knight, a 17-year-old who is Paiute from the Klamath Tribes and trying to become the first female bull rider to compete on the Professional Bull Riders tour. Her upbringing in a small town, riding livestock is a familiar tale across Indian Country.

Growing up, Ed Holyan’s grandma would drop off him and his brother in Coyote Canyon — an isolated and rugged spot on the Navajo Nation — to tend sheep. When they got bored, they’d rope rocks, the Shetland pony and calves with small horns, he said.

“We’d seen my dad rodeo and my older brother rodeoed, so we knew we had the foundation,” said Holyan, the rodeo coach at Diné College in Tsaile, Arizona. “It was in our blood.”

For Kennard Real Bird, who rode saddle broncs for 16 years, horses provided freedom on the Crow reservation in Montana. The river where the Battle of Little Bighorn took place coursed through the land, prairie extended into pine trees and high buttes beckoned with even wider-ranging views.

The ranching life developed into a career as a stock contractor and a reluctant rodeo announcer who deals in observational comedy, including at the Sheridan, Wyoming, rodeo.

No event there is as big of a crowd pleaser than the Indian Relay Races held in July — a contest rooted in buffalo hunts on the Great Plains or raids of camps, depending on who you ask.

A team consists of someone to catch the incoming horse, two people to hold horses and a rider who speeds around the track bareback, twice switching to another horse.

“It’s the most fun you can have with your moccasins on,” Real Bird, 73, jokingly tells crowds.

Kidding aside, horsemanship is a celebrated part of tribes’ history.

On the Crow and Fort Berthold reservations, tribal members compete for the title of ultimate warrior by running, canoeing and bareback horse racing. Back on the Navajo Nation in the Four Corners region, rodeo is still called “ahoohai,” derived from the Navajo word for “chicken.”

The Nueta Hidatsa Sahnish College on the Fort Berthold reservation offers Great Plains horsemanship as a tract in its two-year equine studies program, the only such program at a tribal college or university.

Instructors highlight history like keeping prized horses in an earth lodge and the North Dakota Six Pack, a group of bronc and bull riders that included MHA Nation citizen Joe Chase, who shined on the rodeo circuit in the 1950s, said Lori Nelson, the college’s director of Agriculture and Land Grants.

The tribe recently purchased kid-safe mini bulls and has bucking horses to revive rodeo among the youth, said Jim Baker, who manages the tribe’s Healing Horse Ranch.

“That’s one of our goals to keep the horse culture alive among our people,” he said.

The largest stage for all-Native rodeo competitors is the Indian National Finals Rodeo held in Las Vegas. Tribal regalia, blessings bestowed by elders and flag songs that serve as tribes’ national anthems are as much staples as big buckles and cowboy hats.

Tydon Tsosie, of Crownpoint, New Mexico, restored the town’s moniker to “Navajo Nation Steer Wrestling Capital” when he won the open event there this year as a 17-year-old. In his family, rodeo runs through generations with songs, prayers and respect for horses.

Tsosie plans to continue the tradition, proudly proclaiming, “I see myself doing it for the rest of my life until I get old.”

See all News Updates of the Day

Nevada Tribe Says Coalitions, Not Lawsuits, Will Protect Sacred Sites as US Advances Energy Agenda

RENO, NEV. —

The room was packed with Native American leaders from across the United States, all invited to Washington to hear from federal officials about President Joe Biden’s accomplishments and new policy directives aimed at improving relationships and protecting sacred sites.

Arlan Melendez was not among them.

The longtime chairman of the Reno-Sparks Indian Colony convened his own meeting 4,023 kilometers away. He wanted to show his community would find another way to fight the U.S. government’s approval of a massive lithium mine at the site where more than two dozen of their Paiute and Shoshone ancestors were massacred in 1865.

Opposed by government lawyers at every legal turn, Melendez said another arduous appeal would not save sacred sites from being desecrated.

“We’re not giving up the fight, but we are changing our strategy,” Melendez said.

That shift for the Nevada tribe comes as Biden and other top federal officials double down on their vows to do a better job of working with Native American leaders on everything from making federal funding more accessible to incorporating tribal voices into land preservation efforts and resource management planning.

The administration also has touted more spending on infrastructure and health care across Indian Country.

Many tribes have benefited, including those who led campaigns to establish new national monuments in Utah and Arizona. In New Mexico, pueblos have succeeded in getting the Interior Department to ban new oil and natural gas development on hundreds of square miles of federal land for 20 years to protect culturally significant areas.

But the colony in Reno and others like the Tohono O’odham Nation in Arizona say promises of more cooperation ring hollow when it comes to high-stakes battles over multibillion-dollar “green energy” projects. Some tribal leaders have said consultation resulted in little more than listening sessions, with federal officials not incorporating tribal comments into the decision making.

Rather than pursue its claims in court that the federal government failed to engage in meaningful consultation regarding the lithium mine at Thacker Pass, the Reno-Sparks Indian Colony will focus on organizing a broad coalition to build public support for sacred places.

Tribal members are concerned other culturally significant areas will end up in the path of a modern-day Gold Rush that has companies scouting for lithium and other materials needed to meet Biden’s clean energy agenda.

Melendez was among those thrilled when Biden appointed Deb Haaland to lead the Interior Department. A member of Laguna Pueblo, Haaland is the first Native American to serve as a Cabinet secretary.

Melendez, a former member of the U.S. Human Rights Commission who has led his colony for 32 years, said he understands the difficulty of navigating the electoral landscape in a western swing state where the mining industry’s political clout is second only to the power wielded by casinos.

Still, he was disappointed Haaland declined an invitation to visit the massacre site.

“The largest lithium project in the United States and they don’t even have the time to come out here and meet with the tribal nations in the state of Nevada,” he said.

The tribe’s lawyer, Will Falk, urged other tribes to resist “tricking ourselves into believing that just because the first Native American secretary of Interior is in office that she actually cares about protecting sacred sites.”

Interior Department spokeswoman Melissa Schwartz didn’t respond directly to that criticism but said in an email to The Associated Press that there has been “significant communications and partnership with tribes in Nevada.”

The federal government in early December published new guidance for dealing with sacred sites. While Falk and others are skeptical, they acknowledged the document speaks to concerns tribes have raised for decades.

Among other things, the guidance says federal agencies should involve tribes as early as possible when planning projects to identify potential impacts to sacred sites and to determine whether mitigation measures can allay concerns. Agencies also should consult with tribes that attach significance to the project area, regardless of where they are located.

It also suggests Indigenous knowledge should be on equal footing with other sciences and incorporated into the federal decision-making process. That knowledge can consist of practices, cultural beliefs and oral and written histories that tribes have developed over many generations.

Justin C. Ahasteen, executive director of the Navajo Nation Washington (D.C.) Office, said the new guidance appears to have incorporated some of the recommendations made by tribal leaders but that it could have gone further.

“If this guidebook increases transparency in the consultation process, we will take it as a win,” Ahasteen said. “But ultimately the thing we all seek is for the federal government to acknowledge the necessity of tribal consent before changing rules that affect tribes.”

The problem, Falk said, is none of it is legally binding.

“These kinds of documents function more as pacifying propaganda,” he said.

Western Shoshone Defense Project Director Fermina Stevens said the changes were “more ‘lip service’ for the government to deal with the ‘Indian problem’ in this new day and age of mineral extraction.”

Morgan Rodman, executive director of the White House Council on Native American Affairs, disagrees. He said the guidance is intended to serve as a springboard to improve engagement with tribes and that the administration will be aggressive with training to make sure employees have an understanding of what sacred sites are.

“While change certainly doesn’t happen overnight, it’s part of a continuum of important policy statements — part of the momentum we’ve been building the last three years,” he said in an interview.

Rodman made clear he wasn’t referencing Thacker Pass, but some directives he highlighted have been key points of contention in that case.

U.S. Judge Miranda Du in Reno twice ruled the tribe failed to prove the massacre occurred on the specific grounds of the mining project, or that far-flung tribes had a legal stake in the fight. The 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals upheld her earlier ruling in July.

The tribe says the government has ignored evidence that the land they consider sacred isn’t limited to a specific site where the U.S. Calvary first attacked men, women and children as they slept.

They cited newspaper accounts, diaries and a government surveyor’s report documenting human skulls discovered along a miles-long escape route crossing the mine site where troops killed and scalped those who tried to flee.

Tribal historic preservation officer Michon Eben said the whole stretch is an unmarked burial ground.

Melendez said he’s pleased Biden has promised to enhance consultation.

But if federal agencies don’t follow through, he said, “Well, it’s just words that really don’t mean anything to us.”

Native American News: 2023 in Review

WASHINGTON —

These are some of the Native American-related news stories that made headlines in 2023:

Biden commits to reforms

The White House hosted a third Tribal Nations Summit in December, detailing initiatives and investments in Indian Country over the past three years.

President Joe Biden has nominated or appointed a record number of Native Americans to positions in the federal government. Most recently, the U.S. Senate confirmed his nomination of the first Native American to serve on a federal court, former Cherokee Nation Attorney General Sara Hill.

The Interior Department this year continued its investigation into the federal Indian boarding school system and launched an oral history project to document survivor experiences.

The administration announced 190 new agreements, including deals allowing tribes to comanage federal lands and waters, funding for fish and wildlife restoration and help in mitigating the impact of climate change on tribal land.

Biden issued a new executive order reiterating the administration’s commitment to strengthen the government-to-government relationship with tribes, to give tribes more say in their affairs, and to make it easier for tribes to access funding.

Like others issued in recent years, the order stipulates that it is “not intended to, and does not, create any right, benefit, or trust responsibility, substantive or procedural, enforceable at law or in equity by any party against the United States, its departments, agencies, or entities, its officers, employees, or agents, or any other person.”

Read the administration’s 81-page 2023 progress report to tribal nations here:

SCOTUS upholds ICWA, gives preference to Native adoptive, foster families

Native Americans this year celebrated a major victory in the U.S. Supreme Court after Justices in June affirmed the constitutionality of the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) by a vote of 7 – 2. ICWA is a federal law that sets standards for the removal of Native American children from their homes and directs state welfare agencies to give preference to Native American families when placing Native children in foster or adoptive homes.

Challengers to ICWA say the law is racially discriminatory and deprives states of their rights to manage welfare cases.

Read what this means for tribes here:

Pope Francis officially rejects ‘doctrine of discovery’

The Vatican this year formally repudiated the Doctrine of Discovery, a legal and ideological concept rooted in a series of mid-15th century papal bulls (edicts) giving a blessing for the European conquest of “the New World.”

“Historical research clearly demonstrates that the papal documents in question, written in a specific historical period and linked to political questions, have never been considered expressions of the Catholic faith,” the March 30 statement read. “The church is also aware that… these documents were manipulated for political purposes by competing colonial powers in order to justify immoral acts against Indigenous peoples that were carried out, at times, without opposition from ecclesiastical authorities.”

Institutions pressured to return Native American remains and artifacts

The Interior Department in December issued new rules to spur institutions into complying with the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA).

Passed in 1990, NAGPRA directs all federally funded institutions and federal agencies to catalogue all Native American human remains, funerary items, and objects of cultural significance in their collections; submit the information to a National Park Service database; and work with tribes and Native Hawaiian organizations to repatriate them.

The new rules eliminate a loophole that allowed institutions to hold onto remains they deem “culturally unidentifiable” and extends the deadline for federally funded institutions to complete catalogs of their holdings.

Killers of the Flower Moon: A boost for Native American representation in film

The long-anticipated Martin Scorsese film “Killers of the Flower Moon” opened in October. Based on the 2017 book by David Grann, it explores the “Reign of Terror,” a dark period in 1920’s Oklahoma when a white cattle rancher orchestrated the murders of an untold number of Osage tribe members to get their oil headrights.

Most Native viewers have praised Scorsese for shedding light on acts of genocide against the Osage Nation, for consulting with Osage tribe members and for casting dozens of Osage and other Indigenous Americans as actors and consultants—most notably, Nez Perce/Blackfeet actor Lily Gladstone in a leading role.

Others complained that the story was not told from the perspective of the Osage people but from the view of the white men conspiring to kill them.

Read more:

Record allegations of Indigenous identity theft

They are called “Pretendians,” “Indigenots” or “Wannabindians” — individuals who fabricate Indigenous identity to get ahead in academia, the arts and even government.

This year, Indigenous groups in the U.S. and Canada accused a record number of alleged fake Indians, including a Hollywood producer, university professors, politicians and a horror fiction writer.

But one accusation sent shockwaves around the world. In October, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation reported that singer/songwriter Buffy Sainte-Marie was not Cree from the Piapot First Nation in Saskatchewan but a New Englander of mixed English and Italian ancestry.

Sainte-Marie has strongly denied the report but has removed all references to Indigeneity on her website and declined calls to take a DNA test.

Climate Change Brings Collapsing Stilts and Hungry Bears to Little Diomede Island

WASHINGTON —

Last month, Native Alaskans on Little Diomede Island awoke to see their city office collapsing into the community school next door.

For the Ingalikmiut people [Inupiat] in the Bering Strait, halfway between Siberia and the Alaska mainland, this was the latest crushing evidence of the impact of climate change in the Arctic.

“Looking at the timber and the wood timbers [stilts] that had supported the office building, we didn’t find them to be deteriorating,” explained Sean McKnight, who was part of an inspection team from the Nome-based tribal consortium Kawerak Inc. “Basically, the permafrost is degrading, so building foundations are sinking and sliding.”

Inspectors discovered that several other buildings have also begun to shift downhill.

“Our opinion is that this is going to affect every building in Diomede,” McKnight said.

So, how will Diomeders cope?

“These people have been living here for thousands of years,” McKnight told VOA. “They’re adaptive. They’re resourceful. When they have a problem, they just fix it. This is their home. They have no choice.”

Living on stilts

The city of Diomede, population about 86, consists of three dozen buildings on stilts on the lower slope of an almost vertical cliff. There is a washeteria, where residents shower and do laundry, a health clinic, a small store and a helipad.

In past winters, community members used bulldozers to carve a runway into the ice offshore. This allowed planes to deliver food and supplies. Today, the ice offshore is all new — that is, ice that has not been able to survive a summer melt season.

“The last time we had an ice runway for essential air service was 2014, and that was only for two weeks I believe,” says Diomede tribal coordinator Frances “Sistuq” Ozenna. “Today, we have chopper services year-round. They fly passengers on Mondays, and on Wednesdays, they do mail runs. But the weather always interferes.”

And that can lead to critical shortages of food, medicine and supplies.

“You have to reserve as much as you can, just in case it takes a while for us to get any services to Diomede,” Ozenna told VOA.

That means the tribe must rely more on traditional methods of subsistence, harvesting wild greens, berries or potatoes in spring and seasonal hunting of migrating marine mammals, including walrus and seals.

If the ice is thick enough to cross, that is.

“Food security for Diomede, I think it’s always going to be an issue, because we have limitations in transportation and hunting equipment,” Ozenna says. “You have to know how to survive Diomede. It can get pretty frustrating.”

Undercover predators

In recent years, climate change has introduced a new threat to Diomeders: polar bears, the largest land carnivores on Earth.

Unlike other bear species, polar bears do not hibernate in winter but travel far with the ice in search of seals. Normally at this time of year, they would be far out on the ice, away from human settlements.

But as their habitat melts, they can end up stranded on land.

“You never know when they’re going to come in,” Ozenna said. “They’re most likely to come in at nighttime or during a blizzard, when things are obscured.”

School children are particularly vulnerable, which is why Diomede men will get up early, grab their rifles and patrol the streets, on the lookout for hungry bears.

Diomeder Brendon Ozenna captured this video of a polar bear and her cub attempting to access the community school on November 5, 2021.

After the buildings collapsed, Alaska Governor Mike Dunleavy issued a disaster declaration for Diomede that makes state resources available to help rebuild the city office.

For now, the school’s 22 students have switched to distance learning until after the Christmas holidays.

This, it would seem, is a blessing in disguise — over the past two weeks alone, Ozenna says she has seen three polar bears lurking around town looking for their next meal.

More than 1,000 kilometers northeast of Diomede on Alaska’s northern coast, VOA’s Natasha Mozgovaya reports on permafrost and polar bears in the city of Kaktovik.

NM Extends Ban on Oil and Gas Leasing Around Area Sacred to Native Americans

ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. —

New oil and natural gas leasing will be prohibited on state land surrounding Chaco Culture National Historical Park, an area sacred to Native Americans, for the next 20 years under an executive order by New Mexico Land Commissioner Stephanie Garcia Richard.

Wednesday’s order extends a temporary moratorium that she put in place when she took office in 2019. It covers more than 293 square kilometers of state trust land in what is a sprawling checkerboard of private, state, federal and tribal holdings in northwestern New Mexico.

The U.S. government last year adopted its own 20-year moratorium on new oil, gas and mineral leasing around Chaco, following a push by pueblos and other Southwestern tribal nations that have cultural ties to the high desert region.

Garcia Richard said during a virtual meeting Thursday with Native American leaders and advocates that the goal is to stop the encroachment of development on Chaco and the tens of thousands of acres beyond the park’s boundaries that have yet to be surveyed.

“The greater Chaco landscape is one of the most special places in the world, and it would be foolish not to do everything in our power to protect it,” she said in a statement following the meeting.

Cordelia Hooee, the lieutenant governor of Zuni Pueblo, called it a historic day. She said tribal leaders throughout the region continue to pray for more permanent protections through congressional action.

“Chaco Canyon and the greater Chaco region play an important role in the history, religion and culture of the Zuni people and other pueblo people as well,” she said. “Our shared cultural landscapes must be protected into perpetuity, for our survival as Indigenous people is tied to them.”

The tribal significance of Chaco is evident in songs, prayers and oral histories, and pueblo leaders said some people still make pilgrimages to the area, which includes desert plains, rolling hills dotted with piñon and juniper and sandstone canyons carved by eons of wind and water erosion.

A World Heritage site, Chaco Culture National Historical Park is thought to be the center of what was once a hub of Indigenous civilization. Within park boundaries are the towering remains of stone structures built centuries ago by the region’s first inhabitants, and ancient roads and related sites are scattered further out.

The executive order follows a tribal summit in Washington last week at which federal officials vowed to continue consultation efforts to ensure Native American leaders have more of a seat at the table when land management decisions affect culturally significant areas. New guidance for federal agencies also was recently published to help with the effort.

The New Mexico State Land Office is not required to have formal consultations with tribes, but agency officials said they have been working with tribal leaders over the last five years and hope to craft a formal policy that can be used by future administrations.

The pueblos recently completed an ethnographic study of the region for the U.S. Interior Department that they hope can be used for decision-making at the federal level.