This year marks the 700th anniversary of the death of Marco Polo (1254– 1324), the famous Venetian tourist who presented Asia to the West.

In spite of Marco Polo’s extensive acknowledgment in China, there exists just one strenuous Chinese translation of “The Travels of Marco Polo.” Finished by Feng Chengjun and released by the Shanghai Commercial Press in 1936, this translation disappoints conference modern-day requirements of precision, fluency, and sophistication. Feng summed up each chapter utilizing classical Chinese, sticking to the literary conventions of that period. He relied on a contemporary French edition annotated by A. J. H. Charignon that was itself not constantly precise.

In 2011, Rong Xinjiang, a history teacher at Peking University and a leading scholar of Sino-foreign relations throughout the middle ages duration, united a study hall to annotate “The Travels of Marco Polo.” The group was a who’s who of Chinese medievalists, consisting of specialists on Mongol history, Iranian research studies, and Chinese relations with the Silk Road kingdoms. While their translation– based upon a 1938 edition of the text annotated by A.C. Moule and Paul Pelliot– stays incomplete, their work has actually currently led to several books on Marco Polo, the Silk Road, and middle ages trading centers like the eastern city of Yangzhou.

In late March, Rong took a seat with Sixth Tone for an extensive discussion about his work, the life of Marco Polo, and the unpredictabilities surrounding his story.

Sixth Tone: You are a specialist in Marco Polo research studies. It’s popular that lots of individuals question the credibility of his life and journey. What is your point of view on this?

Rong Xinjiang: Marco Polo certainly existed. His household’s home still stands today. Numerous agreements from his household have actually been maintained in the archives of Venice. Throughout that time, Venice’s business network extended into the eastern Mediterranean. The Polo household was associated with service, developing various industrial stations from West to East. Marco Polo’s famous journeys, a minimum of up until he got in Yuan dynasty China (1279– 1368), can be traced point by point.

In academic community, there is no doubt about the presence of Marco Polo. There has actually been debate concerning whether he in fact went to China. Frances Wood, a British scholar, released the book “Did Marco Polo Go to China?” in 1995. She recommends that Marco Polo may have assembled his travelogue based upon Persian-language trade handbooks and regional reports. Wood’s perspective is not brand-new; the German scholar Herbert Franke proposed a comparable concept in 1973.

In addition, some Chinese scholars have actually explained that if Marco Polo held a main position throughout the Yuan dynasty as he declared, there must matter records in Chinese authorities files. Definitive proof has actually not been discovered hence far.

Sixth Tone: Do you discover these doubtful perspectives persuading?

Rong: The mainstream view in academic community is that Marco Polo did certainly check out China. As early as 1941, Yang Zhijiu found a memorial in the “Yongle Dadian,” a Ming dynasty encyclopedia, that notes the names of 3 envoys sent out to the “Ilkhanate,” in modern-day Iran, which completely matches the pertinent accounts in Marco Polo’s travelogue.

German sinologist Hans Ulrich Vogel released a book entitled “Marco Polo Was in China” in 2012. In this work, Vogel highlights Marco Polo’s comprehensive descriptions of ancient Chinese salt production procedures and his detailed records of Yuan dynasty currency– information hardly ever discovered in other middle ages literature.

Sixth Tone: But as you discussed previously, there are no main Chinese records about Marco Polo. Why is that?

Rong: Keep in mind that “The Travels of Marco Polo” consists of numerous overstated and even fantastical components. Marco Polo did not compose the book himself; it was told to his fellow prisoner, an author, while he was sent to prison in Genoa.

The fundamental structure of the story stays legitimate: Marco Polo took a trip from Venice to Iran, then through Central Asia, the Tarim Basin, the Hexi Corridor, and lastly reached Dadu– contemporary Beijing. He fulfilled Kublai Khan and later on checked out numerous areas in southeastern China before leaving from the port city of Quanzhou with the 3 envoys. He accompanied the princess Kököchin to Persia for her marital relationship, and ultimately went back to his homeland.

When it comes to the absence of main Chinese records about him, I personally concur with the historian Cai Meibiao’s view. Marco Polo did not hold a formal main position; rather, he was an “ortoq.” Ortoqs were an unique merchant group throughout the Mongol Yuan dynasty. Mongol khans, princes, and princesses approved different benefits to ortoqs, enabling them to perform organization or take part in usury utilizing royal cash and tokens. The majority of the earnings were turned over to the court and the khan, however a little part might be kept on their own. There is even a monolith in Quanzhou devoted to a Uyghur ortoq from this duration.

Sixth Tone: So, due to the fact that Marco Polo was an “ortoq” instead of an official court authorities, he is not taped in main historic files.

Rong: Exactly. This title not just discusses why Marco Polo is missing from main records however likewise supplies ideas about his life. If he undoubtedly acted as an ortoq under Kublai Khan, he might have resided in China for a prolonged duration even without understanding Chinese.

Marco Polo most likely did not speak Chinese with complete confidence; his efficiency in Mongolian and Persian would have been sufficient. This likewise discusses why the Chinese city names and referrals in “The Travels of Marco Polo” do not constantly match basic Chinese pronunciation however line up much better with Mongolian and Persian pronunciations.

Sixth Tone: Can you supply an example?

Rong:. There is a location pointed out in “The Travels of Marco Polo” called Cotan, situated in the southwestern area these days’s Tarim Basin. In standard Chinese historic texts, this location is frequently described as “Yutian,” while in the authorities “History of Yuan,” it is called “Odon.” In Muslim historic sources, the name for this location is “Hotan.” Marco Polo’s “Cotan” plainly lines up more carefully with “Hotan” and is rather unique from “Yutian.”

Sixth Tone: In your viewpoint, what is the main worth of Marco Polo’s travelogue?

Rong: The special worth originates from the truth that he was a merchant. In Chinese history, those who thoroughly took a trip and left travelogues generally fall under 2 classifications: spiritual figures, such as the Tang dynasty (618– 907) monks Yijing and Xuanzang, and diplomats like Zheng He (1371– 1433). Merchants’ notes are reasonably limited, however “The Travels of Marco Polo” fills this space.

If you read this book carefully, you’ll discover that Marco Polo observed each location carefully, paying unique attention to regional items and products. He frequently talked about which products would pay if offered in particular areas. It is specifically this merchant’s viewpoint that supplies us with important records about ancient Chinese socio-economic life, unique from main federal government files.

Sixth Tone: Could you offer an upgrade on the development of the Chinese translation of “The Travels of Marco Polo”? You’ve been dealing with it considering that 2011; when do you believe we’ll see it in print?

Rong: Our work surpasses simple translation; it includes comprehensive annotation. When the book is ultimately released, there might be just 2 volumes of equated text, however the annotations might cover 6 or 7 volumes. Let’s take the example of Cotan. We require to supply in-depth annotations about the various variations of this name in different local literature, the historic modifications that the area went through, and why Marco Polo didn’t discuss jade when explaining Cotan. Another example: Marco Polo pointed out that the Mongols had a kind of garment called “nascisi” (“nasij” in Persian), which was made with gold thread and used by nobles, making them shine like gold. There were a number of variations of “nascisi.” Which one did Marco Polo in fact see? All of this needs us to cross-reference historic and historical sources.

You can think of that this is a painstaking and tough job. I think it needs to be done.

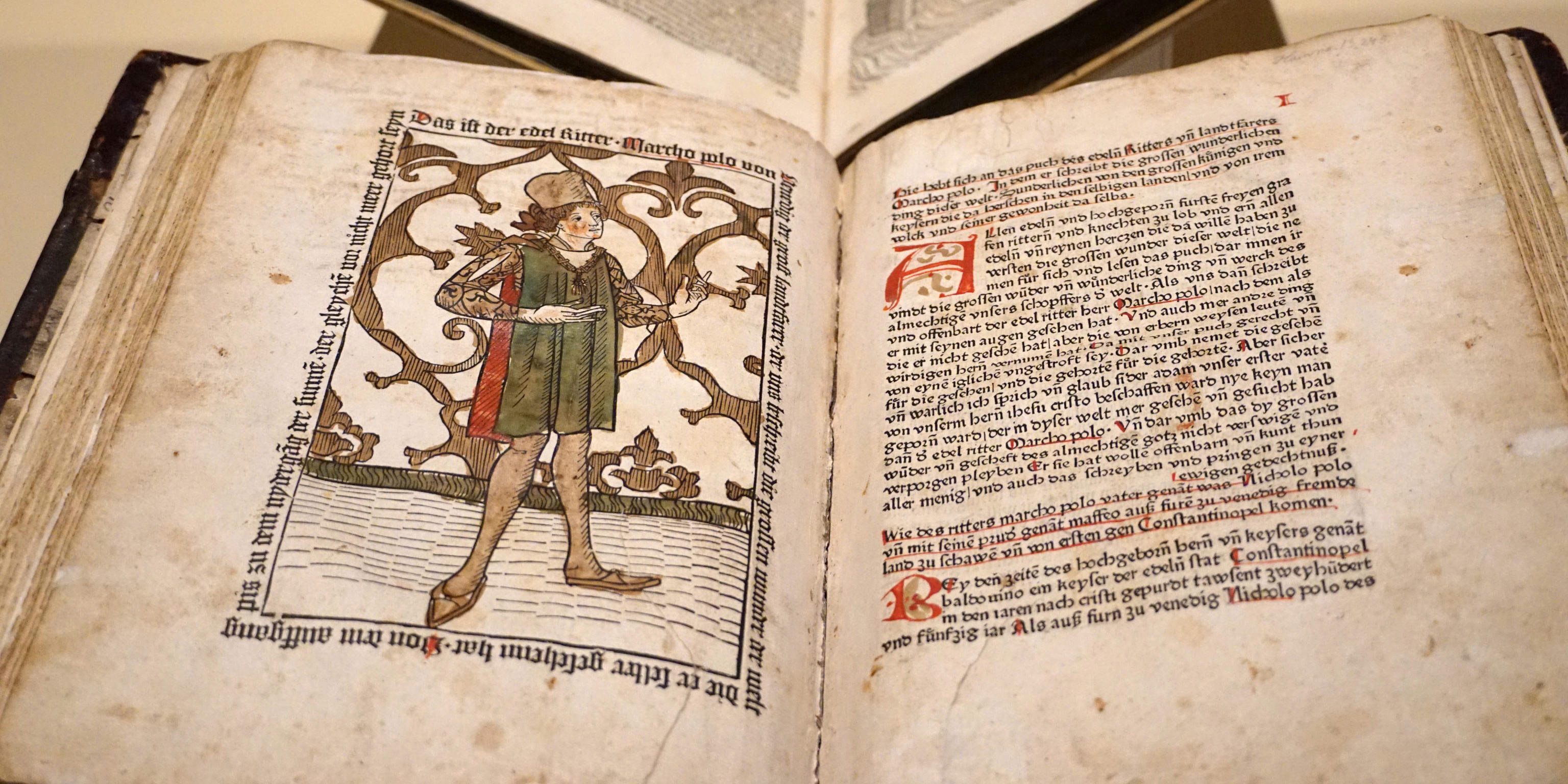

(Header image: A German-language book from the 15th century on display screen throughout an exhibit marking the 700th anniversary of Marco Polo’s death, Venice, Italy, April 5, 2024. Andrea Merola/EPA by means of IC)